Las Vegas — Journalist/author Carl Bernstein is best known for his original reporting about the Watergate scandal for The Washington Post alongside fellow reporter Bob Woodward. He was the keynote speaker at the 2022 Las Vegas Book Festival on Saturday afternoon.

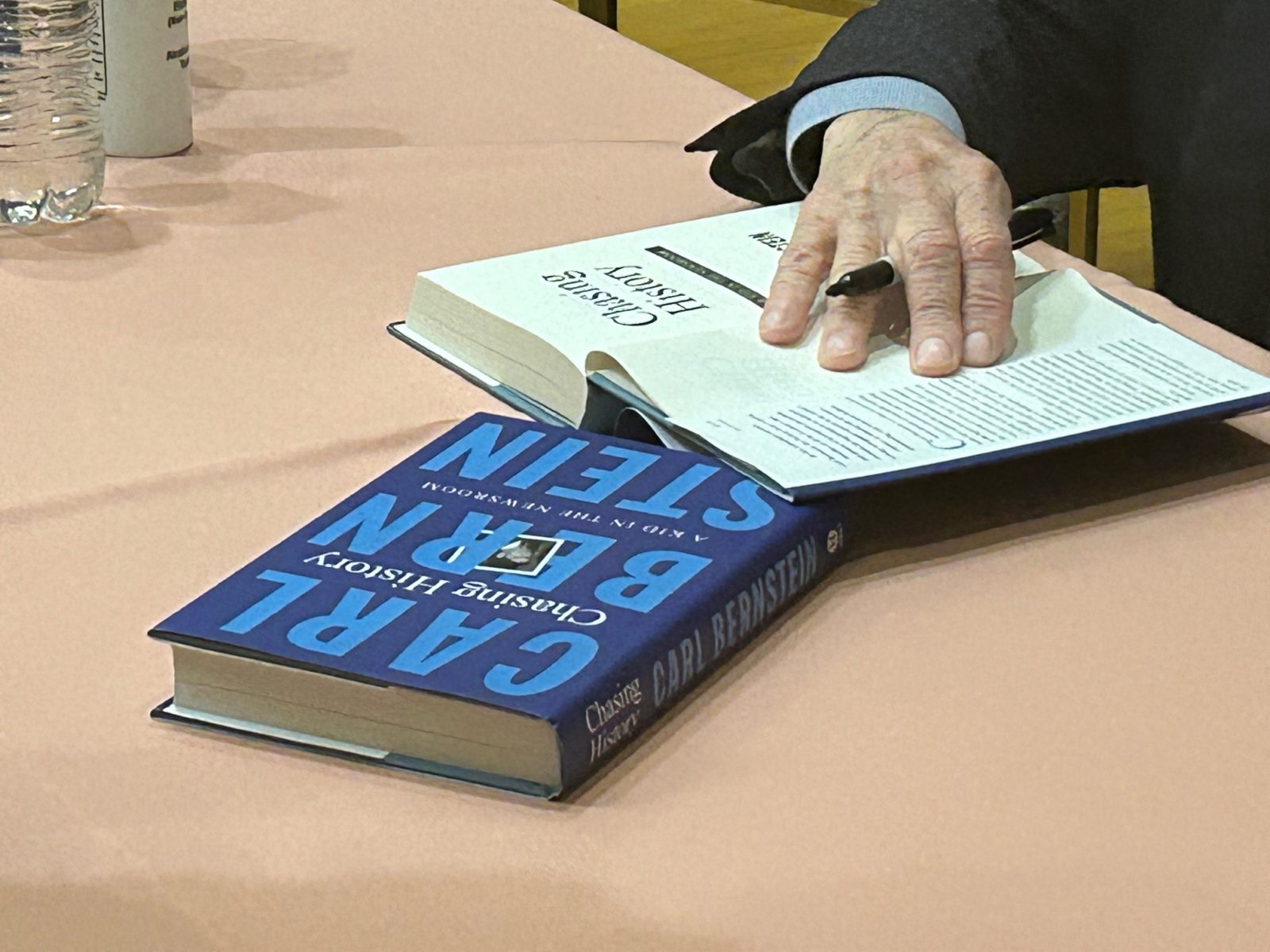

Bernstein has written several books — ranging from “All the President’s Men” to his newest, “Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom.” As someone who has worked in several newsrooms, I was particularly interested in hearing from Bernstein.

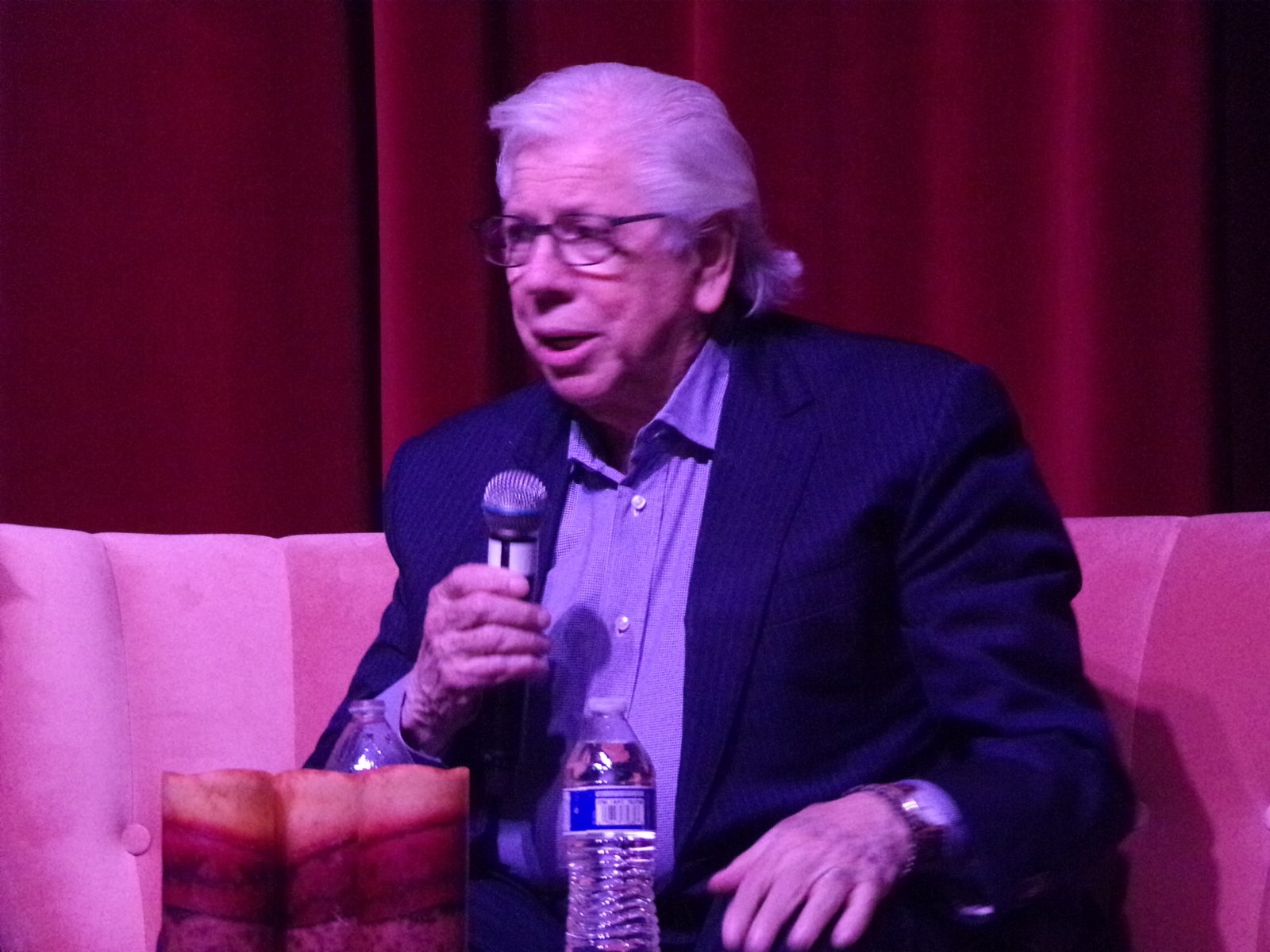

The investigative reporter and author was interviewed on stage by Steve Sebelius, politics and government editor for The Las Vegas Review-Journal newspaper. There were about 150 people in the audience inside the Historic Fifth Street School in downtown Las Vegas.

Here is part of the discussion between Sebelius and Bernstein:

Q: ”I related to a lot of the passages as I too, was a kid in the newsroom, although I didn’t start as young as Mr. Bernstein did at The Washington Star. You started at a very young age, as a teenager, and first saw the newsroom, the chaotic newsroom at The Washington Star. There is a theme that runs throughout the book which is a theme about paying your dues. People don’t start as investigative reporters. They start by paying your dues and you certainly paid your dues…first as a copyboy and then working your way up to doing reporting. Talk a little bit about that, paying your dues.”

A: “I was a terrible student in high school. I said in the book, I had one foot in the pool hall and one foot in the juvenile court and maybe a toe in the classroom. I had a 10th grade journalism course and I could pass some exams by writing essays. My father sort of sensed that I might not make it out of high school. We had a friend who worked at the afternoon newspaper in town and got me an interview for a job. I had taken typing in the 10th grade with the girls. I was sick of shop classes—building all of these meaningless things. So I went for an interview at this great newspaper and I didn’t get hired. I think the guy thought I was probably too short and too young looking to be hired. I kept knocking on the door to go back. After the interview, he took me out to a back door into the newsroom and there was this amazing commotion going on like everyone running and yelling like they were on the most urgent errands in the nation. A copyboy was the lowest level position in the newsroom, copyboys did everything. Then, a copyboy came up with a dolly full of newspapers. He handed me one, it was still warm, and I knew in that moment that’s what I wanted to do with my life.

“I kept knocking on this guy’s door and finally he said, ‘Can you type?’ I said yeah. He said, ‘Go take the typing test and see how you do.’ I got a call the next day, he said, ‘Come to work, you’re hired.’ It was because I could type so fast. Immediately, I was immersed in this enterprise in the capital of the United States where I grew up. Kennedy is running against Nixon for president. It’s the beginning for the real push for civil rights in this country. Within two weeks, I became friends with the state editor of the paper because he lived around the corner from me. Proximity means a lot. If you are lucky, you get a chance because of proximity but it’s what you do with that proximity. Our next door neighbor was Allen Bible, the senator from Nevada, who became a wonderful source for me, at the age of 17. The state editor said to me, ‘Kennedy is coming to your high school tomorrow. Why don’t you go out with a notebook and just takes notes on the crowd? Because you know the terrain there. Our fancy political reporter is great on politics but he doesn’t know the terrain.’ So I did and low and behold, the next day’s story was Kennedy coming to my high school. I described it in the book and about half of the story was from my notes. Everyday, I was exposed to everything that was going on. I would go into the wire room with 20 teletype machines with news from all over the world. I would take it to whatever desk it was supposed to go to. There I was, this kid in a newsroom, doing this with the greatest reporters in the world all around me.”

Q: One thing you said you weren’t that great of a student was your inconstant attendance at university. There was a push at the time to professionalize or ensure that reporters had college degrees and you didn’t have a college degree. That got in the way of being hired full-time at The Star. Your career turned out all right without that degree, wouldn’t you say? Do you think a degree is necessary to be a good reporter?

A: “No. Let me tell you, I think we need a lot more dropouts in newspapers and news organizations. I’m really serious. It was right in the era when newspapers stopped hiring people without a college degree. By the time I dropped out of the University of Maryland, there was a time when they were making some new hires and this great city editor said, ‘Bernstein, managing editor, you can’t do that. Got to have a college degree.’ Meanwhile, I had done everything. By the time I was 21, they still wanted me to have a degree. One of the problems in the news business, conservatives have been much better than liberals about this, newsrooms were not and still not representative enough of our communities and the country…politically, socially, economically. It hurts our news report, it makes us less credible in the long run.

“But it is also particularly true of dropouts. Yes, it’s great that you have a college education. But to have a newsroom with nobody who has had the experience of not going to college or growing up in a different environment that’s just as valuable in the some ways to the news organization or what’s being covered as somebody with a degree. I’m not suggesting that 50 percent of our newsroom ought to be staffed by dropouts. We need to be more representative—but it doesn’t mean race, women, it also means education. Also, I have great belief in vocational education. If I had to judge what Obama’s mistakes were…pushing the idea that everybody has to go to college, I think is a huge mistake. There are great jobs, industrial jobs, tech jobs, all kinds of things and some people don’t want to go to college. To be pushed by your parents or social pressure to go to college, I think is nuts.”

Q: You also discovered, early on, every reporter eventually learns about the presence of your feelings as a person and how they intrude onto the job. You were talking about covering the Kennedy inauguration and just the enchantment of the spectacle of the president, newly inaugurated president on his way to the White House for the first time. You write, ‘It hadn’t occurred to me being a reporter could get so mixed up with feelings.’ There’s a lot of people who think reporters don’t have feelings about anything. But that’s certainly not the case.

A: “No, it’s not. Also, there are two separate questions here. Those two times that I just described, Ike and Kennedy inauguration, were the first two times I saw the president. Although my mother said she took me to Roosevelt’s funeral. To this day, when I go to the White House, I get a little lump in the tummy when I go in there. In terms of feelings, first of all, I think it helps to have strong feelings of all kinds. I went to public school in the District of Columbia, the capital of the United States. I went to legally segregated public schools until I was in the sixth grade when the Brown Decision came down in 1954. Most people don’t realize that we had that in the capital of the United States. As I started to cover the civil rights movement…I used the line in the book that the truth is not neutral. Woodward and I have used this expression for 50 years now about what good reporting is. It’s really the best attainable version of the truth. That does not mean that one side gets 50 percent and the other side gets 50 percent. I mean, a lynching, is not neutral. The truth is not neutral. I think being a reporter is the most subjective of acts. What’s the most important aspect is determining what is news. That’s subjective. This idea that somehow we’ve got to split things down the middle. We have an obligation to be fair not judicious.”

Q: I want to explore this a little more because there was a conflict in journalism now. I think its exemplified by a couple of quotes from the book. The first one…’The ideal was to get as near to the truth as good reporting can take you through assistance, learning and observing with an open mind regardless of your own opinion.’ The second thing is when you were covering the press conference of one woman who was married to one of the civil rights who was missing at the time presumed dead, we now know he was dead. You write, ‘The old 50-50 down the middle, half on one side, half on the other approach was given away to real reporting that was closer to the truth because, for all the right reasons, the truth was not neutral.’ There’s a conflict there. On one hand, you don’t want to impose your own opinion but on the other hand you’re talking about a situation where what is right is overwhelming and obvious. How do journalists today navigate that?

A: “You know, I don’t think it is as hard as it sounds. I think part of being a reporter to get to this question of fairness. I think reporters need to have some native talent to develop. I didn’t have a clue until I met these wonderful people who were older than me and became my mentors. I think reporters tend to be lousy listeners. They just want to get their story in the paper, get it on air. How many times do you see on the best of the network shows or cable…A reporter on Capitol Hill will shove a mic in Mitch McConnell’s face and say, ‘How about this Mr. Minority Leader?’ Shove a mic in Schumer’s face and say, ‘How about this, McConnell says x, y, z.’ Well, Schumer says, ‘McConnell, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ Then, the reporter leaves. He has this manufactured controversy and he hasn’t gone deep into the story. Look, reporters, we all have a preconceived notion, of what the story is when we go out. I have never gone to do a story to match my preconceived notion. Really, it never fit in that easily.

“I thought Watergate, for the first few days, was to go straight to the CIA. I even wrote a long memo. Then, at that point, again, my experience is…remember our information on Watergate, just as Bob has done with Trump or what I have done on Trump on the air, we didn’t get our information from Democrats. They didn’t know a damn thing. It all came from people who worked with Richard Nixon. The same with Trump. You think I’m going to learn from Schumer what Trump is up to? Come on, I talked to Republicans.

“I did a story for CNN and their website in the last year of the Trump presidency saying that at least 21 Republican members in the Senate held Trump in disdain. I’ve been wanting to do this story for a long time because I heard from so many people on their staffs as well as some of the senators how much they think Trump is dangerous and a lot of other things that I’ve put on the air about Trump came from people in the Senate and staff members. Finally, I decided, I can’t sit on this and I don’t have an obligation to the Senators of confidentiality basically because most of my information came from members of staff. I said, I’m going to name them so I named 21 of them and went into great detail. One that I didn’t name that counted the most probably was McConnell who really disdains Trump and has through his whole presidency except McConnell has been able to use Trump for what McConnell really wants which is…One, he really wants to be the majority leader. But two, judges and he succeeded. Think of how crazy these senators are, getting up everyday and defending Trump. Part of the reason where we are is because of this. The next day I get a call from a former Republican senator, who left the Senate a few years early, said the number is really closer to 40.”

The investigative journalist was asked about the fall of newspapers and other newsrooms that were forced to cut their staffs.

“Newspapers are the fabric that held their communities for 100 years,” Bernstein said. “They lost their news organizations they’re not coming back. What we may never get back is covering the high school football team. It’s a huge deal, covering the public library, we’re not gonna get them back. We still can get some of it back. I don’t think the American presidency is ever going to be under reported. I think there’s reason for optimism.“

Bernstein talked about The Texas Tribune online newspaper, which is using a new model of funding. It is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization that can accept donations, corporate sponsorships and foundation grants.

“Woodward and I were just down in Texas for a fundraiser for the Texas Tribune,” he said. “Great reporting is being done by the Texas Tribune not The Austin Statesman. It is a model that The Tribune is trying to take to every state. The potential for non-profit reporting is so great. Incredible reporting. I think the future of reporting is bright in particular for investigative reporting.”

Towards the end of the discussion, Bernstein suggested that young people should volunteer for the military or work in a hospital after graduating from high school.

Sebelius asked: “What can be done culturally?”

Bernstein answered: “I’m not sure… we’ll see. If anything is to be done in this country it’s generational. For kids to do a year or year and a half in military, forest service, work in a hospital. I think it would be transformative.“

Follow Carl Bernstein on his official website at: www.carlbernstein.com. His latest book, “Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom”, is now available everywhere books are sold.

A discussion between Steve Sebelius and Carl Bernstein at the Las Vegas Book Festival

Steve Sebelius is the politics editor at the Las Vegas Review-Journal

Investigative journalist/author Carl Bernstein

About 150 people were in the audience to watch the discussion

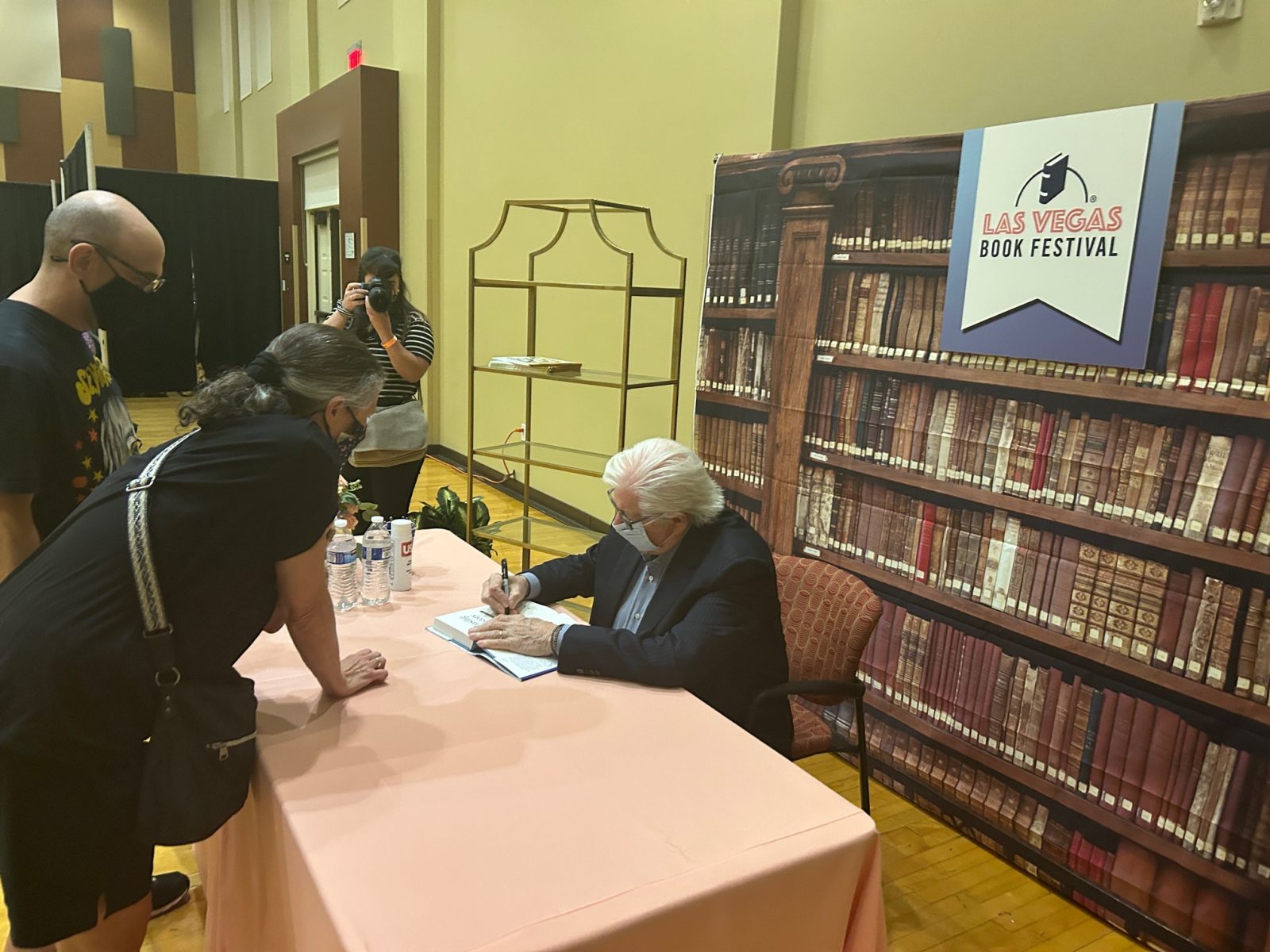

Autograph session with Bernstein after the discussion

His newest book is “Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom”

AmericaJR’s Jason Rzucidlo poses for a photo with Carl Bernstein